Ported to Cloud with Winglang (Part One)

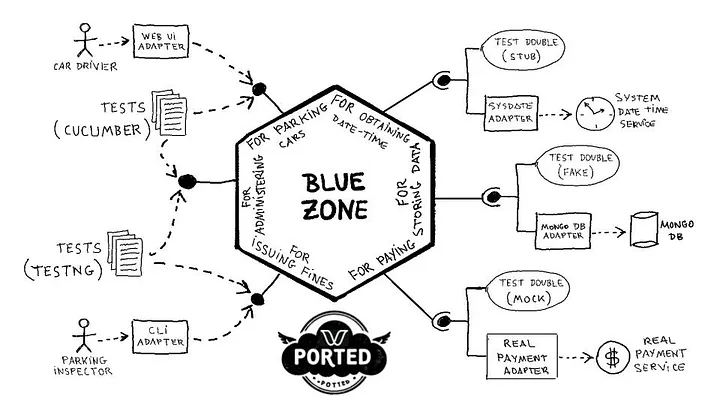

Blue Zone Application from “Hexagonal Architecture Explained

Fig 1: The “Blue Zone” Application Ported to Cloud with Wing

Directly porting software applications to the cloud often results in inefficient and hard-to-maintain code. However, using the new cloud-oriented programming language Wing in combination with Hexagonal Architecture has proven to be a winning combination. This approach strikes the right balance between cost, performance, flexibility, and security.

In this series, I will share my experiences migrating various applications from mainstream programming languages to Winglang. My first experience implementing the Hexagonal Architecture in Wing was reported in the article "Hello, Winglang Hexagon!”. While it was enough to acquire confidence in this combination, it was built on an oversimplified "Hello, World" greeting service, and as such lacked some essential ingredients and was insufficient to prove the ability of such an approach to work at scale.

In Part One, I focus on porting the “Blue Zone” application, featured in the recently published book “Hexagonal Architecture Explained”, from Java to Wing. The “Blue Zone” application brings in a substantial code base, still not too huge to dive into unmanageable complexity, yet representative of a large class of applications. Also, the fact that it was originally written in mainstream Java brings an interesting case study of creating a cloud-native variant of such applications.

This report also serves as a tribute to Juan Manuel Garrido de Paz, the book's co-author, who sadly passed away in April 2024.

Before we proceed, let's recap the fundamentals of the Hexagonal Architecture pattern.

The Hexagonal Architecture Pattern Essentials

Refer to Chapter Two of the “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book for a detailed and formal pattern description. Here, I will bring an abridged recap of the main sense of the pattern in my own words.

The Hexagonal Architecture pattern suggests a simple yet practical approach to separate concerns in software. Why is the separation of concerns important? Because the software code base quickly grows even for a modest in terms of delivered value application. There are too many things to take care of. Preserving cognitive control requires a high-level organization in groups or categories. To confront this challenge the Hexagonal Architecture pattern suggests splitting all elements involved in a particular software application into five distinct categories and dealing with each one separately:

- The Application itself. This category encapsulates the real value delivered to prospective customers and users. This is the reason why software is going to be developed and used in the first place. Sometimes, it’s called the Core or System Under Development (SuD). Another possible name for this part could be Computation - where external inputs are processed and final results are produced. Visually, the Application part of the system is represented in the form of a hexagon. There is nothing special or magic in this shape. As the “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book authors explain:

“Hexagonal Architecture” has served well as a hook to the pattern. It’s easy to remember and generates conversation. However, in this book we want to be correct: The name of the pattern is “Ports & Adapters”, because there really are ports, and there really are adapters, and your architecture will show them.

-

External Actors that communicate with or are communicated by the Application. These could be human end users, electronic devices, or other Applications. The original pattern suggests further separation into Primary (or Driving) Actors - those who initiate an interaction with the Application, and Secondary (or Driven) Actors - those with whom the Application initiates communication.

-

Ports - a fancy name for formal specification of Interfaces the Primary Actors could use (aka Driving Ports) or Secondary Actors need to implement (aka Driven Ports) to communicate with the Application. In addition to the formal specification of the interface verbs (e.g.

BuyParkingTicket) Ports also provide detailed specifications of data structures that are exchanged through these interfaces. -

Adapters fill the gaps between External Actors and Ports. As the name suggests, Adapters are not supposed to perform any meaningful computations, but rather basically convert data from/to formats the Actors understand to/from data ****the Application understands.

-

Configurator pulls everything together by connecting External Actors to the Application through Ports using corresponding Adapters. Depending on the architectural decisions made and price/performance/flexibility requirements these decisions were trying to address, a specific Configuration can be produced statically before the Application deployment or dynamically during the Application run.

Contrary to popular belief, the pattern does not imply that one category, e.g. Application, is more important than others, nor does it suggest ultimately that one should be larger while others smaller. Without Ports and Adapters, no Application could be practically used. Relative sizes are often determined by non-functional requirements such as scalability, performance, cost, availability, and security.

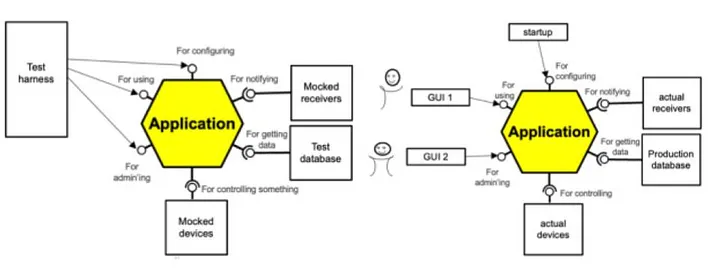

The pattern suggests reducing complexity and risk by focusing on one problem at a time, temporally ignoring other aspects. It also suggests a practical way to ensure the existence of multiple configurations of the same computation each one addressing some specific needs be it test automation or operation in different environments.

The picture below from “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book nicely summarizes all main elements of the pattern:

Fig 2: The Hexagonal Architecture Patterns in a Nutshell

“Blue Zone” Sample Application

From the application README:

BlueZone allows car drivers to pay remotely for parking cars at regulated zones in a city, instead of paying with coins using parking meters.

- Driving actors using the application are car drivers and *parking inspectors.

- Car drivers will access the application using a Web UI (User Interface), and they can do the following:

- Ask for the available rates in the city, in order to choose the one of the zone they want to park the car at.

- Buy a ticket for parking the car during a period of time at a regulated zone. This period starts at current date-time. The ending date-time is calculated from the paid amount, according to the rate (euros/hour) of the zone.

- Parking inspectors will access the application using a terminal with a CLI (Command Line Interface), and they can do the following:

- Check a car for issuing a fine, in case that the car is illegally parked at a zone. This will happen if there is no active ticket for the car and the rate of the zone. A ticket is active if current date-time is between the starting and ending date-time of the ticket period.

- Driven actors needed by the application are:

- Repository with the data (rates and tickets) used in the application. It also has a sequence for getting ticket codes as they are needed.

- Payment service that allows the car driver to buy tickets using a card. Obviously, no adapter for a real service has been developed, just a test-double (mock).

- Date-time service for obtaining the current date-time when needed, for buying a ticket and for checking a car.

I chose this application for two primary reasons. First, it was recommended by the “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book as a canonical example. Second, it was originally developed in Java. I was curious to see what is involved in porting a non-trivial Java application to the cloud using the Wing programming language.

Where Do You Start From?

The “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book provides reasonable recommendations in Chapter 4.9, “What is development sequence?”. It makes sense to start with “Test-to-Test” and proceed further. However, I did what most software engineers normally do— starting with translating the Java code to Wing. Within a couple of part-time days, I reached a stage where I had something working locally in Wing with all external interfaces simulated.

While technically it worked, the resulting code was far too big relative to the size of the application, hard to understand even for me, aesthetically unappealing, and completely non-Wingish. Then, I embarked on a two-week refactoring cycle, looking for the most idiomatic expression of the core pattern ideas adapted to the Wing language and cloud environment specifics.

What comes next is different from how I worked. It was a long series of chaotic back-and-forth movements with large portions of code produced, evaluated, and scrapped. This usually happens in software development when dealing with unfamiliar technology and domains.

Finally, I’ve come up with something that hopefully could be gradually codified into a more structured and systematic process so that it will be less painful and more productive the next time. Therefore, I will present my findings in the conceptually desirable sequence to be used next time, rather than how it happened in reality.

Thou Shalt Start with Tests

To be more accurate, the best and most cost-effective way is to start with a series of acceptance tests for the system's architecturally essential use cases. Chapter 5.1 of the “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book, titled “How does this relate to use cases?”, elaborates on the deep connection between use case modeling and Hexagonal Architecture. It’s worth reading carefully.

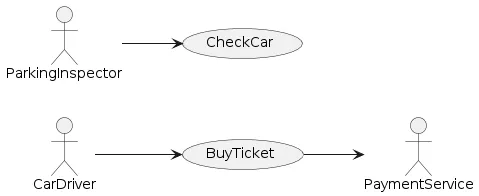

Even the previous statement wasn’t 100% accurate. We are supposed to start with identifying Primary External Actors and their most characteristic ways of interacting with the system. In the case of the “Blue Zone” application, there are two Primary External Actors:

- Card Driver

- Parking Inspector

For the Car Drive actor, her primary use case would be “Buy Ticket”; for the Parking Inspector, his primary use case would be “Check Car”. By elaborating on these use cases’ implementation we will identify Secondary External Actors and the rest of the elements.

The preliminary use case model resulting from this analysis is presented below:

Fig 3: “Blues Zone” Application Use Case Mode

Notice that the diagram above contains only one Secondary Actor - the Payment Service and does not include any internal Secondary Actors such as a database. While these technology elements will eventually be isolated from the Application by corresponding Driven Ports they do not represent any Use Case External Actor, at least in traditional interpretation of Use Case Actors.

Specifying use case acceptance criteria before starting the development is a very effective technique to ensure system stability while performing internal restructurings. In the case of the “Blue Zone” application, the use case acceptance tests were specified in Gherkin language using the Cucumber for Java framework.

Currently, a Cucumber framework for Wing does not exist for an obvious reason - it’s a very young language. While an official Cucumber for JavaScript does exist, and there is a TypeScript Cucumber Tutorial I decided to postpone the investigation of this technology and try to reproduce a couple of tests directly in Wing.

Surprisingly, it was possible and worked fairly well, at least for my purposes. Here is an example of the Buy Ticket use case happy path acceptance test specified completely in Wing:

bring "../src" as src;

bring "./steps" as steps;

/*

Use Case: Buy Ticket

AS

a car driver

I WANT TO

a) obtain a list of available rates

b) submit a "buy a ticket" request with the selected rate

SO THAT

I can park the car without being fined

*/

let _configurator = new src.Configurator("BuyTicketFeatureTest");

let _testFixture = _configurator.getForAdministering();

let _systemUnderTest = _configurator.getForParkingCars();

let _ = new steps.BuyTicketTestSteps(_testFixture, _systemUnderTest);

test "Buy ticket for 2 hours; no error" {

/* Given */

["name", "eurosPerHour"],

["Blue", "0.80"],

["Green", "0.85"],

["Orange", "0.75"]

]);

_.next_ticket_code_is("1234567890");

_.current_datetime_is("2024/01/02 17:00");

_.no_error_occurs_while_paying();

/* When */

_.I_do_a_get_available_rates_request();

/* Then */

_.I_should_obtain_these_rates([

["name", "eurosPerHour"],

["Blue", "0.80"],

["Green", "0.85"],

["Orange", "0.75"]

]);

/* When */

_.I_submit_this_buy_ticket_request([

["carPlate", "rateName", "euros", "card"],

["6989GPJ", "Green", "1.70", "1234567890123456-123-062027"]

]);

/* Then */

_.this_pay_request_should_have_been_done([

["euros", "card"],

["1.70", "1234567890123456-123-062027"]

]);

/* And */

_.this_ticket_should_be_returned([

["ticketCode", "carPlate", "rateName", "startingDateTime", "endingDateTime", "price"],

["1234567890", "6989GPJ", "Green", "2024/01/02 17:00", "2024/01/02 19:00", "1.70"]

]);

/* And */

_.the_buy_ticket_response_should_be_the_ticket_stored_with_code("1234567890");

}

While it’s not a truly human-readable text, it’s close enough and not hard to understand. There are quite a few things to unpack here. Let’s proceed with them one by one.

The Test Structure

The test above assumes a particular project folder structure and reflects the Wing module and import conventions, which states

It's also possible to import a directory as a module. The module will contain all public types defined in the directory's files. If the directory has subdirectories, they will be available under the corresponding names.

From the first two lines, we can conclude that the project has two main folders: src where all source code is located, and test where all tests are located. Further, there is a test\steps subfolder where individual test step implementations are kept.

The next three lines allocate a preflight Configurator object and extract from it two pointers:

_testFixturepointing to a preflight class responsible for the test setup_systemUnderTestwhich points to a Primary Port Interface intended for Car Drivers.

Within the “Buy ticket for 2 hours; no errors”, we allocate an inflight BuyTicketTestSteps object responsible for implementing individual steps. Conventionally, this object gets an almost invisible name underscore, which improves the overall test readability. This is a common technique for developing a Domain-Specific Language (DSL) embedded in a general-purpose host language.

It’s important to stress, that while it did not happen in my case, it’s fully conceivable to start the project with a simple src and test\steps folder structure and a simple test setup to drive other architectural decisions.

Of course, with no steps implemented, the test will not even pass compilation. To make progress, we need to look inside the BuyTicketTestSteps class.

Test Steps Class

The test steps class for the Buy Ticket Use Case is presented below:

bring expect;

bring "./Parser.w" as parse;

bring "./TestStepsBase.w" as base;

bring "../../src/application/ports" as ports;

pub class BuyTicketTestSteps extends base.TestStepsBase {

_systemUnderTest: ports.ForParkingCars;

inflight var _currentAvailableRates: Set<ports.Rate>;

inflight var _currentBoughtTicket: ports.Ticket?;

new(

testFixture: ports.ForAdministering,

systemUnderTest: ports.ForParkingCars

) {

super(testFixture);

this._systemUnderTest = systemUnderTest;

}

inflight new() {

this._currentBoughtTicket = nil;

this._currentAvailableRates = Set<ports.Rate>[];

}

pub inflight the_existing_rates_in_the_repository_are(

sRates: Array<Array<str>>

): void {

this.testFixture.initializeRates(parse.Rates(sRates).toArray());

}

pub inflight next_ticket_code_is(ticketCode: str): void {

this.testFixture.changeNextTicketCode(ticketCode);

}

pub inflight no_error_occurs_while_paying(): void {

this.testFixture.setPaymentError(ports.PaymentError.NONE);

}

pub inflight I_do_a_get_available_rates_request(): void {

this._currentAvailableRates = this._systemUnderTest.getAvailableRates();

}

pub inflight I_should_obtain_these_rates(sRates: Array<Array<str>>): void {

let expected = parse.Rates(sRates);

expect.equal(this._currentAvailableRates, expected);

}

pub inflight I_submit_this_buy_ticket_request(sRequest: Array<Array<str>>): void {

let request = parse.BuyRequest(sRequest);

this.setCurrentThrownException(nil);

this._currentBoughtTicket = nil;

try {

this._currentBoughtTicket = this._systemUnderTest.buyTicket(request);

} catch err {

this.setCurrentThrownException(err);

}

}

pub inflight this_ticket_should_be_returned(sTicket: Array<Array<str>>): void {

let sTicketFull = Array<Array<str>>[

sTicket.at(0).concat(["paymentId"]),

sTicket.at(1).concat([this.testFixture.getLastPayResponse()])

];

let expected = parse.Ticket(sTicketFull);

expect.equal(this._currentBoughtTicket, expected);

}

pub inflight this_pay_request_should_have_been_done(sRequest: Array<Array<str>>): void {

let expected = parse.PayRequest(sRequest);

let actual = this.testFixture.getLastPayRequest();

expect.equal(actual, expected);

}

pub inflight the_buy_ticket_response_should_be_the_ticket_stored_with_code(code: str): void {

let actual = this.testFixture.getStoredTicket(code);

expect.equal(actual, this._currentBoughtTicket);

}

pub inflight an_error_occurs_while_paying(error: str): void {

this.testFixture.setPaymentError(parse.PaymentError(error));

}

pub inflight a_PayErrorException_with_the_error_code_that_occurred_should_have_been_thrown(code: str): void {

//TODO: make it more specific

let err = this.getCurrentThrownException()!;

log(err);

expect.ok(err.contains(code));

}

pub inflight no_ticket_with_code_should_have_been_stored(code: str): void {

try {

this.testFixture.getStoredTicket(code);

expect.ok(false, "Should never get there");

} catch err {

expect.ok(err.contains("KeyError"));

}

}

}

This class is straightforward: it parses the input data, uniformly presented as Array<Array<str>>, into application-specific data structures, sends them to either testFixture or _systemUnderTest objects, keeps intermediate results, and compares expected vs actual results where appropriate.

The only specifics to pay attention to are the proper handling of preflight and inflight definitions. I’m grateful to Cristian Pallares, who helped me to make it right.

We have three additional elements with clearly delineated responsibilities:

- Parser - ****Responsible for converting a uniform array of string inputs to the application-specific data structures.

- Test Fixture - ****Responsible for backdoor communication with the system for preconditions setting and postconditions verification.

- System Under Test - ****Responsible for implementing the application logic.

Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Parser

The source code of the Parser module is presented below:

bring structx;

bring datetimex;

bring "../../src/application/ports" as ports;

pub class Util {

pub inflight static Rates(sRates: Array<Array<str>>): Set<ports.Rate> {

return unsafeCast(

structx.fromFieldArray(

sRates,

ports.Rate.schema()

)

);

}

pub inflight static BuyRequest(

sRequest: Array<Array<str>>

): ports.BuyTicketRequest {

let requestSet: Set<ports.BuyTicketRequest> = unsafeCast(

structx.fromFieldArray(

sRequest,

ports.BuyTicketRequest.schema()

)

);

return requestSet.toArray().at(0);

}

pub inflight static Tickets(

sTickets: Array<Array<str>>

): Set<ports.Ticket> {

return unsafeCast(

structx.fromFieldArray(

sTickets,

ports.Ticket.schema(),

datetimex.DatetimeFormat.YYYYMMDD_HHMM

)

);

}

pub inflight static Ticket(sTicket: Array<Array<str>>): ports.Ticket {

return Util.Tickets(sTicket).toArray().at(0);

}

pub inflight static PayRequest(

sRequest: Array<Array<str>>

): ports.PayRequest {

let requestSet: Set<ports.PayRequest> = unsafeCast(

structx.fromFieldArray(

sRequest,

ports.PayRequest.schema()

)

);

return requestSet.toArray().at(0);

}

pub inflight static CheckCarRequest(

sRequest: Array<Array<str>>

): ports.CheckCarRequest {

let requestSet: Set<ports.CheckCarRequest> = unsafeCast(

structx.fromFieldArray(

sRequest,

ports.CheckCarRequest.schema()

)

);

return requestSet.toArray().at(0);

}

pub inflight static CheckCarResult(

sResult: Array<Array<str>>

): ports.CheckCarResult {

let resultSet: Set<ports.CheckCarResult> = unsafeCast(

structx.fromFieldArray(

sResult, ports.CheckCarResult.schema()

)

);

return resultSet.toArray().at(0);

}

pub inflight static DateTime(dateTime: str): std.Datetime {

return datetimex.parse(

dateTime,

datetimex.DatetimeFormat.YYYYMMDD_HHMM

);

}

pub inflight static PaymentError(error: str): ports.PaymentError {

return Map<ports.PaymentError>{

"NONE" => ports.PaymentError.NONE,

"GENERIC_ERROR" => ports.PaymentError.GENERIC_ERROR,

"CARD_DECLINED" => ports.PaymentError.CARD_DECLINED

}.get(error);

}

}

This class, while not sophisticated from the algorithmic point of view, reflects some important architectural decisions with far-reaching consequences.

First, it announces a dependency on the system Ports located in the src\application\ports folder. Chapter 4.8 of the “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book, titled “Where do I put my files?”, makes a clear statement:

The folder structure is not covered by the pattern, nor is it the same in all languages. Some languages (Java), require interface definitions. Some (Python, Ruby) don't. And some, such as Smalltalk, don't even have the concept of files!

It warns, however, that “we’ve observed that folder structures that don't match the intentions of the pattern end up causing damage”. For strongly typed languages like Java, it recommends keeping specifications of Driving and Driven Ports in separate folders.

I started with such a structure, but very soon realized that it just enlarges the size of the code and prevents it from taking full advantage of the Wing module and import conventions. Based on this I decided to keep all Ports in one dedicated folder. Considering the current size of the application, this decision looks justified.

Second, it exploits an undocumented Wing module and import feature that makes all public static inflight methods of a class named Util directly accessible by the client modules, which improves the code readability.

Third, it uses two Wing Standard Library extensions, datetimex, and structx developed to compensate for some features I needed. These extensions were part of my “In Search for Winglang Middleware” project endor.w, I reported about here, here, and here.

Justification for these extensions will be clarified when we look at the core architectural decision about representing the Port Interfaces and Data.

Representing Port Interfaces and Data

Traditional strongly typed Object-Oriented languages like Java advocate encapsulating all domain elements as objects. If I followed this advice, the Ticket object would look something like this:

pub inflight class Ticket {

pub ticketCode: str;

pub carPlate: str;

pub rateName: str;

pub startingDateTime: std.Datetime;

pub endingDateTime: std.Datetime;

pub price: num;

pub paymentId: str;

new (ticketCode: str, ...) {

this.ticketCode = ticketCode;

...

}

pub toJson(): Json {

return Json {

ticketCode = this.ticketCode,

...

}

pub static fromJson(data: Json): Ticket {

return new Ticket(

data.get("ticketCode").asStr(),

...

);

}

pub toFieldArray(): Array<str> {

return [

this.ticketCode,

...

];

}

pub static fromFieldArray(records: Array<Array<str>>): Set<Ticket> {

let result = new MutSet<Ticket>[];

for record in records {

result.add(new Ticket(

record.at(0),

...

);

}

return result.copy();

}

} such

Such an approach introduces 6 extra lines of code per data field for initialization and conversation plus some fixed overhead of method definition. This creates a significant boilerplate overhead.

Mainstream languages like Java and Python try alleviating this pain with various meta-programming automation tools, such as decorators, abstract base classes, or meta-classes.

In Wing, all this proved to be sub-optimal and unnecessary, provided minor adjustments were made to the Wing Standard Library.

Here is how the Ticket data structure can be defined:

pub struct Ticket { //Data structure representing objects

//with the data of a parking ticket:

ticketCode: str; //Unique identifier of the ticket;

//It is a 10-digit number with leading zeros

//if necessary

carPlate: str; //Plate of the car that has been parked

rateName: str; //Rate name of the zone where

//the car is parked at

startingDateTime: std.Datetime; //When the parking period begins

endingDateTime: std.Datetime; //When the parking period expires

price: num; //Amount of euros paid for the ticket

paymentId: str; //Unique identifier of the payment

//made to get the ticket.

}

In Wing, structures are immutable by default, and that eliminates a lot of access control problems.

Without any change, the Wing Standard Library will support out-of-the-box Json.stringify(ticket) serialization to Json string and Ticket.fromJson(data) de-serialization. That’s not enough for the following reasons:

- For data storage, we need conversion of the

Ticketobjects toJsonrather than aJson string Jsonserialization and de-serialization functions need to handle thestd.Datetimefields correctly. Currently theJson.stringify()will convert anystd.Datetimeto an ISO string, butTicket.fromJson()will fail.- To support test automation and different CSV formats, we need the ability to convert data structures to and from an array of strings.

- There is a need for a more flexible conversion of strings to

std.Datetime. For example, the “Blue Zone” application uses the YYYYMM HH:MM format.

All these additional needs were addressed in two Trusted Wing Libraries: datetimex and struct. While the implementation was not trivial and required a good understanding of how Wing and TypeScript interoperability works, it was doable with reasonable effort. Hopefully, these extensions can be included in future versions of the Wing Standard Library.

The special, unsafeCast function helped to overcome the Wing strong type checking limitations. To provide better support for actual vs expected comparison in tests, I decided that fromFieldArray(...) will return Set<...> objects. Occasionally it required toArray() conversion, but I found this affordable.

Now, let’s take a look at the main _systemUnderTest object.

ForParkingCars Port

Following the “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book recommendations, port naming adopts the ForActorName convention. Here is how it is defined for the ParkingCar External Actor:

pub struct BuyTicketRequest { //Input data needed for buying a ticket

//to park a car:

carPlate: str; //Plate of the car that has been parked

rateName: str; //Rate name of the zone where the car is parked at

euros: num; //Euros amount to be paid

card: str; //Card used for paying, in the format 'n-c-mmyyyy', where

// 'n' is the card number (16 digits)

// 'c' is the verification code (3 digits),

// 'mmyyyy' is the expiration month and year (6 digits)

}

/**

* DRIVING PORT (Provided Interface)

*/

pub inflight interface ForParkingCars {

/**

* @return A set with the existing rates for parking a car in regulated

* zones of the city.

* If no rates exist, an empty set is returned.

*/

getAvailableRates(): Set<rate.Rate>;

/**

* Pay for a ticket to park a car at a zone regulated by a rate,

* and save the ticket in the repository.

* The validity period of the ticket begins at the current date-time,

* and its duration is calculated in minutes by applying the rate,

* based on the amount of euros paid.

* @param request Input data needed for buying a ticket.

* @see BuyTicketRequest

* @return A ticket valid for parking the car at a zone regulated by the rate,

* paying the euros amount using the card.

* The ticket holds a reference to the identifier of the payment

* that was made.

* @throws BuyTicketRequestException

* If any input data in the request is not valid.

* @throws PayErrorException

* If any error occurred while paying.

*/

buyTicket (request: BuyTicketRequest): ticket.Ticket;

}

As with Ticket and Rate objects, the BuyTicketRequest object is defined as a plain Wing struct relying on the automatic conversion infrastructure described above.

The ForParkingCars is defined as the Wing interface. Unlike the original “Blue Zone” implementation, this one does not include BuyTicketRequest validation in the port specification. This was done on purpose.

While strong object encapsulation would encourage including the validate() method in the BuyTicketRequest class, with open immutable data structures like the ones adopted here, it could be done where it belongs - in the use case implementation. On the other hand, including the request validation logic in port specification brings in too many implementation details, too early.

ForAdministering Port

This one is used for providing testFixture functionality, and while it is long, it is also completely straightforward:

bring "./Rate.w" as rate;

bring "./Ticket.w" as ticket;

bring "./ForPaying.w" as forPaying;

/**

* DRIVING PORT (Provided Interface)

* For doing administration tasks like initializing, load data in the repositories,

* configuring the services used by the app, etc.

* Typically, it is used by:

* - Tests (driving actors) for setting up the test-fixture (driven actors).

* - The start-up for initializing the app.

*/

pub inflight interface ForAdministering {

/**

* Load the given rates into the data repository,

* deleting previously existing rates if any.

*/

initializeRates(newRates: Array<rate.Rate>): void;

/**

* Load the given tickets into the data repository,

* deleting previously existing tickets if any.

*/

initializeTickets(newTickets: Array<ticket.Ticket>): void;

/**

* Make the given ticket code the next to be returned when asking for it.

*/

changeNextTicketCode(newNextTicketCode: str): void;

/**

* Return the ticket stored in the repository with the given code

*/

getStoredTicket(ticketCode: str): ticket.Ticket;

/**

* Return the last request done to the "pay" method

*/

getLastPayRequest(): forPaying.PayRequest;

/**

* Return the last response returned by the "pay" method.

* It is an identifier of the payment made.

*/

getLastPayResponse(): str;

/**

* Make the probability of a payment error the "percentage" given as a parameter

*/

setPaymentError(errorCode: forPaying.PaymentError): void;

/**

* Return the code of the error that occurred when running the "pay" method

*/

getPaymentError(): forPaying.PaymentError;

/**

* Set the given date-time as the current date-time

*/

changeCurrentDateTime(newCurrentDateTime: std.Datetime): void;

}

Now, we need to dive one level deeper and look at the application logic implementation.

Implementation Details

ForParkingCarsBackend

bring "../../application/ports" as ports;

bring "../../application/usecases" as usecases;

pub class ForParkingCarsBackend impl ports.ForParkingCars {

_buyTicket: usecases.BuyTicket;

_getAvailableRates: usecases.GetAvailableRates;

new(

dataRepository: ports.ForStoringData,

paymentService: ports.ForPaying,

dateTimeService: ports.ForObtainingDateTime

) {

this._buyTicket = new usecases.BuyTicket(dataRepository, paymentService, dateTimeService);

this._getAvailableRates = new usecases.GetAvailableRates(dataRepository);

}

pub inflight getAvailableRates(): Set<ports.Rate> {

return this._getAvailableRates.apply();

}

pub inflight buyTicket(request: ports.BuyTicketRequest): ports.Ticket {

return this._buyTicket.apply(request);

}

}

This class resides in the src/outside/backend folder and provides an implementation of the ports.ForParkingCars interface that is suitable for a direct function call. As we can see, it assumes two additional Secondary Ports: ports.ForStoringData and ports.ForObtainingTime and delegates actual implementation to two Use Case implementations: BuyTicket and GetAvailableRates. The BuyTicket Use Case implementation is where the core system logic resides, so let’s look at it.

BuyTicket Use Case

bring math;

bring datetimex;

bring exception;

bring "../ports" as ports;

bring "./Verifier.w" as validate;

pub class BuyTicket {

_dataRepository: ports.ForStoringData;

_paymentService: ports.ForPaying;

_dateTimeService: ports.ForObtainingDateTime;

new(

dataRepository: ports.ForStoringData,

paymentService: ports.ForPaying,

dateTimeService: ports.ForObtainingDateTime

) {

this._dataRepository = dataRepository;

this._paymentService = paymentService;

this._dateTimeService = dateTimeService;

}

pub inflight apply(request: ports.BuyTicketRequest): ports.Ticket {

let currentDateTime = this._dateTimeService.getCurrentDateTime();

this._validateRequest(request, currentDateTime);

let paymentId = this._paymentService.pay(

euros: request.euros,

card: request.card

);

let ticket = this._buildTicket(request, paymentId, currentDateTime);

this._dataRepository.saveTicket(ticket);

return ticket;

}

inflight _validateRequest(request: ports.BuyTicketRequest, currentDateTime: std.Datetime): void {

let requestErrors = validate.BuyTicketRequest(request, currentDateTime);

if requestErrors.length > 0 {

throw exception.ValueError(

"Buy ticket request is not valid",

requestErrors

);

}

}

inflight _buildTicket(

request: ports.BuyTicketRequest,

paymentId: str,

currentDateTime: std.Datetime

): ports.Ticket {

let ticketCode = this._dataRepository.nextTicketCode();

let rate = this._dataRepository.getRateByName(request.rateName);

let endingDateTime = BuyTicket._calculateEndingDateTime(

currentDateTime,

request.euros,

rate.eurosPerHour

);

return ports.Ticket {

ticketCode: ticketCode,

carPlate: request.carPlate,

rateName: request.rateName,

startingDateTime: currentDateTime,

endingDateTime: endingDateTime,

price: request.euros,

paymentId: paymentId

};

}

/**

* minutes = (euros * minutesPerHour) / eurosPerHour

* endingDateTime = startingDateTime + minutes

*/

static inflight _calculateEndingDateTime(

startingDateTime: std.Datetime,

euros: num,

eurosPerHour: num

): std.Datetime {

let MINUTES_PER_HOUR = 60;

let minutes = math.round((MINUTES_PER_HOUR * euros) / eurosPerHour);

return datetimex.plus(startingDateTime, duration.fromMinutes(minutes));

}

}

The “Buy Ticket” Use Case implementation class resides within the src/application/usescases folder. It returns an inflight function responsible for executing the Use Case logic:

- Validate Request

- Pay for a new

Ticket - Create the

Ticketrecord - Store the

Ticketrecord in the database

The main reason for implementing Use Cases as inflight functions is that all Wing event handlers are inflight functions. While direct function calls are useful for local testing, they will typically be HTTP REST or GraphQL API calls in a real deployment.

The actual validation of the BuyTicketRequest is delegated to an auxiliary Util class within the Verifier.w module. The main reason is that individual field validation might be very detailed and involve many low-level specifics, contributing little to the overall use case logic understanding.

Pulling all Components Together

Following the “Hexagonal Architecture Explained” book recommendations, this is implemented within a Configurator class as follows:

bring util;

bring endor;

bring "./outside" as outside;

bring "./application/ports" as ports;

enum ApiType {

DIRECT_CALL,

HTTP_REST

}

enum ProgramType {

UNKNOWN,

TEST,

SERVICE

}

pub class Configurator impl outside.BlueZoneApiFactory {

_apiFactory: outside.BlueZoneApiFactory;

new(name: str) {

let mockService = new outside.mock.MockDataRepository();

let programType = this._getProgramType(name);

let mode = this._getMode(programType);

let apiType = this._getApiType(programType, mode);

this._apiFactory = this._getApiFactory(

name,

mode,

apiType,

mockService,

mockService,

mockService

);

}

_getProgramType(name: str): ProgramType { //TODO: migrate to endor??

if name.endsWith("Test") {

return ProgramType.TEST;

} elif name.endsWith("Service") || name.endsWith("Application") {

return ProgramType.SERVICE;

} elif std.Node.of(this).app.isTestEnvironment {

return ProgramType.TEST;

}

return ProgramType.UNKNOWN;

}

_getMode(programType: ProgramType): endor.Mode {

if let mode = util.tryEnv("MODE") {

return Map<endor.Mode>{ //TODO Migrate this function to endor

"DEV" => endor.Mode.DEV,

"TEST" => endor.Mode.TEST,

"STAGE" => endor.Mode.STAGE,

"PROD" => endor.Mode.PROD

}.get(mode);

} elif programType == ProgramType.TEST {

return endor.Mode.TEST;

} elif programType == ProgramType.SERVICE {

return endor.Mode.STAGE;

}

return endor.Mode.DEV;

}

_getApiType(

programType: ProgramType,

mode: endor.Mode,

): ApiType {

if let apiType = util.tryEnv("API_TYPE") {

return Map<ApiType>{

"DIRECT_CALL" => ApiType.DIRECT_CALL,

"HTTP_REST" => ApiType.HTTP_REST

}.get(apiType);

} elif programType == ProgramType.SERVICE {

return ApiType.HTTP_REST;

}

let target = util.env("WING_TARGET");

if target.contains("sim") {

return ApiType.DIRECT_CALL;

}

return ApiType.HTTP_REST;

}

_getApiFactory(

name: str,

mode: endor.Mode,

apiType: ApiType,

dataService: ports.ForStoringData,

paymentService: ports.ForPaying,

dateTimeService: ports.ForObtainingDateTime

): outside.BlueZoneApiFactory {

let directCall = new outside.DirectCallApiFactory(

dataService,

paymentService,

dateTimeService

);

if apiType == ApiType.DIRECT_CALL {

return directCall;

} elif apiType == ApiType.HTTP_REST {

return new outside.HttpRestApiFactory(

name,

mode,

directCall

);

}

}

pub getForAdministering(): ports.ForAdministering {

return this._apiFactory.getForAdministering();

}

pub getForParkingCars(): ports.ForParkingCars {

return this._apiFactory.getForParkingCars();

}

pub getForIssuingFines(): ports.ForIssuingFines {

return this._apiFactory.getForIssuingFines();

}

}

This is an experimental, still not final, implementation, but it could be extended to address the production deployment needs. It adopts a static system configuration by exploiting the Wing preflight machinery.

In this implementation, a special MockDataStore object implements all three Secondary Ports: data service, paying service, and date-time service. It does not have to be this way and was created to save time during the scaffolding development.

The main responsibility of the Configuratior class is to determine which type of API should be used:

- Direct call

- Local HTTP REST

- Remote HTTP REST

- Local HTTP REST plus HTML

- Remote HTTP REST plus HTML

The actual API creation is delegated to corresponding ApiFactory classes.

What is remarkable about such an implementation is that the same test suite is used for all configurations, except for real HTML-based UI mode. The latter could also be achieved but would require some HTML test drivers like Selenium.

It is the first time I have achieved such a level of code reuse. As a result, I run local direct call configuration most of the time, especially when I perform code structure refactoring, with full confidence that it will run in a remote test and production environment without a change. This proves that the Wing cloud-oriented programming language and Hexagonal Architecture is truly a winning combination.

The Big Picture

Including the full source code of every module would increase this article's size too much. Access to the GitHub repository for this project is available on demand.

Instead, I will present the overall folder structure, two UML class diagrams, and a cloud resources diagram reflecting the main program elements and their relationships.

The Folder Structure

├── src

│ ├── application

│ │ ├── ports

│ │ │ ├── ForAdministering.w

│ │ │ ├── ForIssuingFines.w

│ │ │ ├── ForObtainingDateTime.w

│ │ │ ├── ForParkingCars.w

│ │ │ ├── ForPaying.w

│ │ │ ├── ForStoringData.w

│ │ │ ├── Rate.w

│ │ │ └── Ticket.w

│ │ ├── usecases

│ │ │ ├── BuyTicket.w

│ │ │ ├── CheckCar.w

│ │ │ ├── GetAvailableRates.w

│ │ │ └── Veryfier.w

│ ├── outside

│ │ ├── backend

│ │ │ ├── ForAdministeringBackend.w

│ │ │ ├── ForIssuingFinesBackend.w

│ │ │ └── ForParkingCarsBackend.w

│ │ ├── http

│ │ │ ├── html

│ │ │ │ ├── _htmlForParkingCarsFormatter.ts

│ │ │ │ └── htmlForParkingCarsFormatter.w

│ │ │ ├── json

│ │ │ │ ├── jsonForIssuingFinesFormatter.w

│ │ │ │ └── jsonForParkingCarsFormatter.w

│ │ │ ├── ForIssuingFinesClient.w

│ │ │ ├── ForIssuingFinesController.w

│ │ │ ├── ForParkingCarsClient.w

│ │ │ ├── ForParkingCarsController.w

│ │ │ └── middleware.w

│ │ ├── mock

│ │ │ └── MockDataRepository.w

│ │ ├── ApiFactory.w

│ │ ├── BlueZoneAplication.main.w

│ │ ├── DirectCallApiFactory.w

│ │ └── HttpRestApiFactory.w

│ └── Configurator.w

├── test

│ ├── steps

│ │ ├── BuyTicketTestSteps.w

│ │ ├── CheckCarTestSteps.w

│ │ ├── Parser.w

│ │ └── TestStepsBase.w

│ ├── usecase.BuyTicketTest.w

│ └── usecase.CheckCarTest.w

├── .gitignore

├── LICENSE

├── Makefile

├── README.md

├── package-lock.json

├── package.json

└── tsconfig.json

Fig 4: Folder Structure

Application logic-wise the project is small. Yet, it is already sizable to pose enough challenges for cognitive control over its structure. The current version attempts to strike a reasonable balance between multiple criteria:

- Maximal depth of file structure.

- Complexity and amount of import statements.

- The ratio between code that delivers intended value and code required to organize, test, and deliver it.

While computing all sets of desirable metrics is beyond the scope of this publication, one back-of-envelope calculation could be performed here and now manually: the percentage of files under the application and outside folders, including intermediate folders (let’s call “value”) and the total number of files and folders (let’s call it “stuff”). In the current version, the numbers are:

Total: 55

src/application: 16

src/: 41

Files: 43

Strict Value to Stuff Ratio: 16*100/55 = 29.09%

Extended Value to Stuff Ratio: (15+19)*100/42 = 74.55%

Is it big or little? Good or Bad? It’s hard to say at the moment. The initial impression is that the numbers are healthy, yet coming up with more founded conclusions needs additional research and experimentation. A real production system will require a significantly larger number of tests.

From the cognitive load perspective, 43 files is a large number exceeding the famous 7 +/- 2 limit of human communication channels and short memory. It requires some organization. In the current version, the maximal number of files at one level is 8 - within the limit.

The presented hierarchical diagram only partially reflects the real graph picture - cross-file dependencies resulting from the bring statement are not visible. Also, the __node_files__ folder reflecting external dependencies and having an impact on resulting package size is omitted as well.

In short, without additional investment in tooling and methodology of metrics, the picture is only partial.

We still can formulate some desirable direction: we prefer to deal as much as possible with assets generating the direct value and as little as possible with supporting stuff required to make it work. Ideally, a healthy Value to Stuff ratio would come from language and library support. Automatic code generation, including that performed by Generative AI, would reduce the typing but not the overall cognitive load.

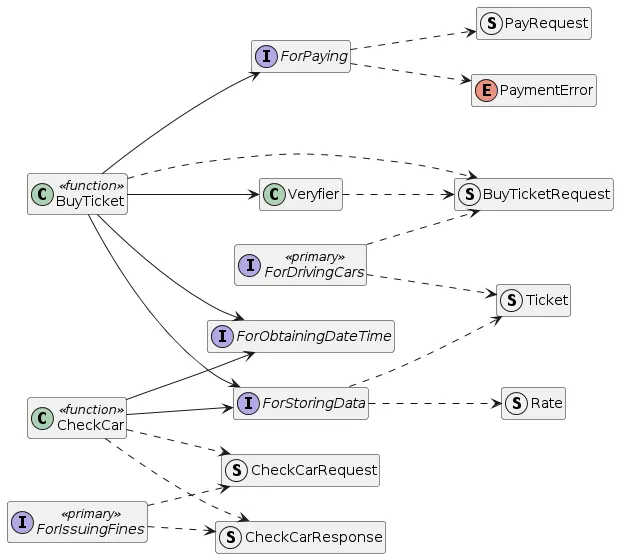

Class Diagram

Depicting all “Blue Zone” application elements in a single UML Class Diagram would be impractical. Among other things, UML does not support directly separate representation of preflight and inflight elements. We can visualize separately the most important parts of the system. For example, here is a UML Class Diagram for the application part:

Fig 5: `src/application` Class Diagram

DO NOT PUBLISH

@startuml

left to right direction

hide members

struct Ticket

struct Rate

struct BuyTicketRequest

interface ForDrivingCars <<primary>>

ForDrivingCars ..> BuyTicketRequest

ForDrivingCars ..> Ticket

interface ForStoringData

ForStoringData ..> Rate

ForStoringData ..> Ticket

struct PayRequest

enum PaymentError

interface ForPaying

ForPaying ..> PayRequest

ForPaying ..> PaymentError

interface ForObtainingDateTime

class BuyTicket <<function>>

class Veryfier

Veryfier ..> BuyTicketRequest

BuyTicket --> Veryfier

BuyTicket ..> BuyTicketRequest

BuyTicket --> ForObtainingDateTime

BuyTicket --> ForStoringData

BuyTicket --> ForPaying

interface ForIssuingFines <<primary>>

struct CheckCarRequest

struct CheckCarResponse

ForIssuingFines ..> CheckCarRequest

ForIssuingFines ..> CheckCarResponse

class CheckCar <<function>>

CheckCar --> ForStoringData

CheckCar --> ForObtainingDateTime

CheckCar ..> CheckCarRequest

CheckCar ..> CheckCarResponse

@enduml

Notice that the IForParkingCars and ForIssuingFines primary interfaces are named differently from the Car Driver and Parking Inspector primary actors and BuyTicket and CheckCar use cases. This is not a mistake. Primary Port Interface names should reflect the Primary Actor role in a particular use case. There are no automatic rules for such a naming. Hopefully, the selected names are intuitive enough.

Notice also, that the Primary Interfaces are not directly implemented within the application module and there is a disconnect between these interfaces and use case implementations.

This is also not a mistake. The concrete connection between the Primary Interface and the corresponding use case implementation depends on configuration, as reflected in the UML Class Diagram Below:

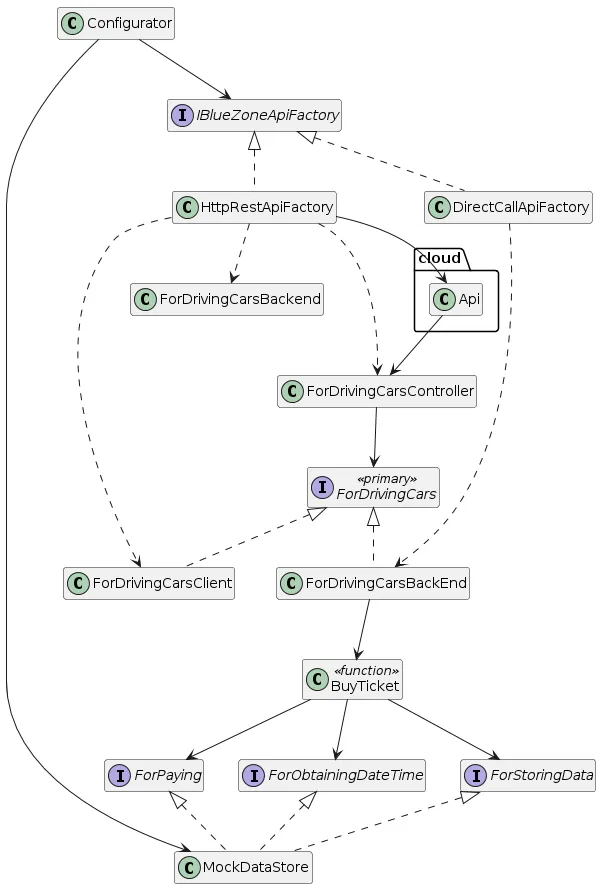

Fig 6: Configurator Class Diagram (”Buy Ticket” Use Case only)

DO NOT PUBLISH

@startuml

hide members

interface ForDrivingCars <<primary>>

interface ForStoringData

interface ForPaying

interface ForObtainingDateTime

class BuyTicket <<function>>

BuyTicket --> ForObtainingDateTime

BuyTicket --> ForStoringData

BuyTicket --> ForPaying

class ForDrivingCarsBackEnd implements ForDrivingCars

ForDrivingCarsBackEnd --> BuyTicket

class ForDrivingCarsClient implements ForDrivingCars

class ForDrivingCarsController

ForDrivingCarsController --> ForDrivingCars

class MockDataStore implements ForStoringData, ForPaying, ForObtainingDateTime

interface IBlueZoneApiFactory

class DirectCallApiFactory implements IBlueZoneApiFactory

DirectCallApiFactory ..> ForDrivingCarsBackEnd

class HttpRestApiFactory implements IBlueZoneApiFactory

class cloud.Api

cloud.Api --> ForDrivingCarsController

HttpRestApiFactory --> cloud.Api

HttpRestApiFactory ..> ForDrivingCarsController

HttpRestApiFactory ..> ForDrivingCarsClient

HttpRestApiFactory ..> ForDrivingCarsBackend

class Configurator

Configurator --> IBlueZoneApiFactory

Configurator --> MockDataStore

@enduml

Only elements related to the “Buy Ticket” Use Case implementation and essential connections are depicted to avoid clutter.

According to the class diagram above the Configurator will decide which IBlueZoneApiFactory implementation to use: DirectApiCallFactory for local testing purposes or HttpRestApiFactory for both local and remote testing via HTTP and production deployment.

Cloud Resources

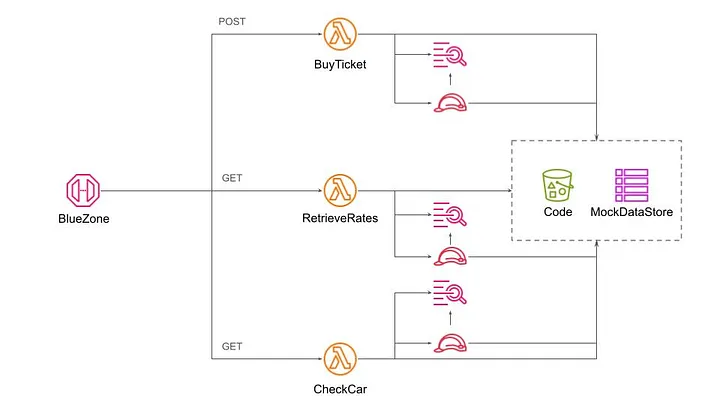

Fig 7: Cloud Resources

The cloud resources diagram presented above reflects the outcome of the Wing compilation to the AWS target platform. It is quite different from the UML Class Diagram presented above and we have to conclude that various types of diagrams complement each other. The Cloud Resources diagram is important for understanding and controlling the system's operational aspects like cost, performance, reliability, resilience, and security.

The main challenge, as with previous diagrams, is the scale. With more cloud resources, the diagram will quickly be cluttered with too many details.

The current versions of all diagrams are more like useful illustrations than formal blueprints. Striking the right balance between accuracy and comprehension is a subject for future research. I addressed this issue in one of my early publications. Probably, it’s time to come back to this research topic.

Conclusion

The experience of porting the “Blue Zone” application, featured in the recently published book “Hexagonal Architecture Explained”, from Java to Wing led to the following interim conclusions

- Directly porting software applications to the cloud often results in inefficient and hard-to-maintain code.

- Each programming language has its idiomatic way of expressing design decisions and blind translation from one to another does not work either.

- Implementing the Hexagonal Architecture pattern in the new cloud-oriented programming language Wing has proven to be a winning combination. This approach strikes the right balance between cost, performance, flexibility, and security.

- Codebase size grows fast for even a modest functionality-wise speaking application. Keeping the complexity under control requires methodology and guidelines.

- Graphical representations of the application logic and cloud resources are useful for illustration. Turning them into formal blueprints requires additional research.

Acknowledgments

Throughout the preparation of this publication, I utilized several key tools to enhance the draft and ensure its quality.

The initial draft was crafted with the organizational capabilities of Notion's free subscription, facilitating the structuring and development of ideas.

For grammar and spelling review, the free version of Grammarly proved useful for identifying and correcting basic errors, ensuring the readability of the text.

The enhancement of stylistic expression and the narrative coherence checks were performed using the paid version of ChatGPT 4o. The ChatGPT 4o tool was also used to develop critical portions of the Trusted Wing Libraries: datetimex and struct in TypeScript.

UML Class Diagrams were produced with the free version of the PlantText UML online tool.

Java version of the “Blue Zone” application was developed by Juan Manuel Garrido de Paz, the book’s co-author. Juan Manuel Garrido de Paz sadly passed away in April 2024. May his memory be blessed and this report serves as a tribute to him.

While all advanced tools and resources significantly contributed to the preparation process, the concepts, solutions, and final decisions presented in this article are entirely my own, for which I bear full responsibility.